Inherited cancer mutations

Dr.M.Raszek

Cancer inherited predisposition

October is breast cancer awareness month and lots of activities are happening in support of educating women about the best protection against this disease. In no other group is this more relevant than to women with the inherited predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer.

Breast cancer now boasts a very high treatment success rate. In fact, the treatment of breast cancers has been so successful over the years, that scientists and clinicians are finally discussing the possibility of starting to mention that certain cancers can indeed be cured. There are many factors influencing this trend of improved cancer survival, and DNA sequencing to a degree has been spearheading this advancement due to the development of cancer personalized medicines treatments provided to cancer patients based on their genetic makeup.

Women with an inherited predisposition purportedly tend to have worse outcomes than the general breast cancer population. Believe it or not, the confirmation of this scientifically still awaits. One analysis of published literature on this topic suggested only a small difference in the survival rates for carriers of BRCA1 and 2 genes as compared to other breast cancer patients. On the one hand, perhaps that can be a sigh of relief for the women in affected families. On the other hand, try explaining that to family members where the majority of all women died under the age of 50. There must be other confounding genetic and environmental factors that determine the likelihood of negative outcomes for those with an inherited cancer predisposition.

Thus, to coincide with breast cancer awareness month, and upon the invitation of the Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Society to present at their upcoming symposium, I investigated the latest literature on the topic of cancer predisposing mutations. As always, science weaves an interesting story to tell.

How common is heritable cancer?

Inherited predispositions for breast and ovarian cancer is often quoted in range of 5-15%, and many factors can influence such outcomes. Some of the members of the HBOCS I spoke to think that the actual figure in the population might be even higher than what is currently proposed.

I looked at the recently published largest study to investigate inherited cancer mutations. This study is quite enormous in its scale at the moment, including 10,389 patients. That is a large group data, and typically the larger the group, the greater the accuracy of the risk estimate. This group of patients spanned 33 types of cancer in total. Based on the entire group, about 8% of all cancers are hereditary. However, different cancers demonstrated wide differences. Cholangiocarcinoma (cancer of the bile duct), showed the least inherited predisposition with inherited (germline), mutations seen in 2% of cancer cases. The highest level that was observed was 22% of inherited predisposition in the Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (neuroendocrine cancer affecting hormone and nerve pathways).

It appeared that 10% of breast cancer patients have inherited predisposition mutations in their DNA, and 20% of ovarian cancers patients have inherited predisposition mutations. So my friends at HBOCS had the right idea.

However, as you are about to find out, not surprisingly, this study investigated DNA sequencing primarily using gene panels. I wrote about gene panels previously when discussing the clinical utility of genome sequencing. Gene panels are preselected genes within the genome that are investigated, and what genes are chosen to be investigated depends on the disease. In the medical world, gene panels rule the diagnostic world and they are predominantly used. The gene panel that investigates all of the genes in the genome is called an exome, and exomes are slowly replacing gene panels as a tool to investigate DNA, including cancer. The primary advantage to this is that more information is captured and one is not limited by our lack of knowledge about which genes are contributing to disease development. Even if we don’t know now, the information is captured for future use. And the knowledge of each mutation’s contribution to disease is growing very rapidly.

The same logic applies as to why the remainder of the genome should also be investigated, and the step above gene panels is whole genome sequencing which captures all of the DNA information, including all of the genes (only about 2% of the genome), as well as all of the sequence in between. Whole genome sequencing certainly has its proponents and is also slowly creeping into medical use despite the increased cost and complexity. But currently it is still considered a novelty, despite the recognized benefit of investigating the entire DNA for health predispositions.

Real life cancer DNA testing

Another large group study I focused on contained the data that came out of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Such data is so valuable because we can see it in action in hospitals around the world. Overall 10,336 cancer patients consented to DNA testing, which is a massive number. No doubt these studies will only grow larger, but that is an amazing investment to help cancer patients, and since sequencing is not cheap, so these are great achievements. On top of that, 1,044 of these patients were also directed by their doctors to germline mutation testing. In other words, 10% of these cancer patients were also tested for inherited cancer predisposing mutations.

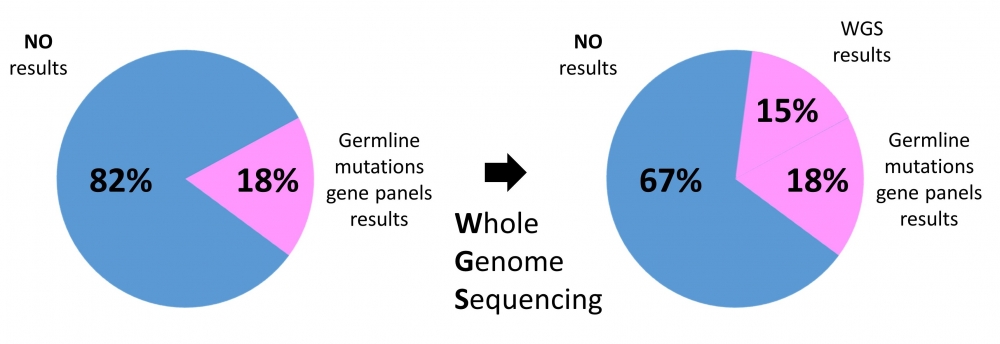

Out of this smaller group of 1,044 patients, 18% had inherited mutations that were “actionable”, meaning some intervention method is available to them. Or another way to put it, 18% of these cancer patients might gain access to new treatment options from investigating their DNA sequence.

Of those 18% of cancer patients that can now benefit from access to new treatment or management options, 55% would not meet the criteria to be legible for such testing. That means that more than half of those cancer patients with new valuable data for their medical management would be denied testing based on our current medical guidelines of choosing who is eligible for such testing. Many specialists have already commented on the fact that our current guidelines for patient selection for genetic testing of cancer predisposition are inadequate because of the number of people that are left behind.

But let us continue with this study group because this is foreshadowing what we can expect to be the norm for all cancer patients in the future. Once again, of those 18% of patients that received actionable genetic results, the majority of them displayed mutations in genes involved in DNA repair, with about one third of all patients showing mutations affecting BRCA genes.

All of these patients had also their tumors DNA sequenced, and the comparison of inherited mutations as well the acquired mutations that contributed to cancer development were analyzed to determine a potential therapy course. And here comes the limitation of the current screening guidelines: of the 18% of cancer patients that showed inherited predisposing mutations, 21% could benefit from a specific type of treatment based on the uncovered DNA mutations; nearly half of these cancer patients would have been missed if only screened based on current guidelines. That means potentially lifesaving treatment would never become available to them. If you like to learn more about tumor sequencing for acquired mutations, I wrote about this topic previously.

How many mutated genes can lead to cancer?

The above study pointed out how prevalent mutations in BRCA genes actually are across different cancers, not just breast and ovarian cancers. This was definitely well demonstrated in the first science article I quoted, with breast and ovarian cancers showing the largest frequencies of BRCA mutations. However it also showed that there are many other genes involved, in all of the cancers combined, that can contribute either to the hereditary predisposition of cancer, or cancer through randomly acquired mutations.

That in fact brought me to another question: how many genes do we know of that are found mutated in cancers? And how many of these mutated genes can be inherited as a potential predisposition to cancer?

The investigation I found suggested that currently there are at least 609 cancer genes, and 280 of these genes also show a heritable cancer predisposition that can be passed on from generation to generation. Considering that each gene could have literally thousands of different mutation outcomes, that is a lot of genetic material that could be affected in cancer patients and that would be beneficial to be tested.

The best way to capture all of that information, including all genetic sites contributing to cancer, whether already known or not, is through genome sequencing.

Genome sequencing of cancer

Whole genome sequencing is beneficial not just for capturing all of the information in one go for future prosperity. The fact that whole genome sequencing captures complete DNA information allows one to find problems that are otherwise not captured by gene panels, as well as having that information available immediately. One great example of that is research recently spearheaded by the Cambridge University where 440 patients with multiple primary tumors that did not show any results with past genetic testing were also analyzed using whole genome sequencing for any inherited predisposition mutations. Despite the much smaller group size than other quoted studies, this was the first such study of its kind.

This study had a couple of measures. The first was to see the genetics behind multiple primary tumors. The second was to show what whole genome sequencing can uncover after prior limited cancer genetic testing. What did they find? Despite the past genetic testing of these cancer patients, important germline mutations were still uncovered in 15% of patients! This means that basically whole genome sequencing could double the rate of discovery of predisposing mutations in cancer patients. Based on the past quoted success rate of gene panels, the authors estimated that one third of cancer patients could have informative DNA mutations.

More importantly, about 3% of patients showed important DNA mutations findings related to their cancer in more than one gene! This is still not something that is appreciated much, but this additional level of genetic complexity can be influencing patient outcomes. In the past, cancer patients were frequently just screened for one gene at a time, most often BRCA genes, and even currently used gene panels can vary dramatically for what DNA regions are investigated. How likely is it that these important findings of double or more mutations are missed in testing? Imagine how challenging the treatment of such patients might be with such complex genetic backgrounds if the oncologist does not even have a clue about this background information?

There are many reasons why genome sequencing can uncover these additional genetic problems that might not be found with conventional gene panels. One of the obvious reasons is that it decodes much more DNA, including regions that are never analyzed with gene panels but that could still contribute to disease development. That includes DNA information outside genes and in between gene fragments. Another benefit is that genome sequencing can allow for a more advanced analysis of what is referred to as structural variations, or mutations that affect large areas of the DNA code. Gene panels are typically not well-configured to uncover such malformations. I recently wrote extensively on the topic of structural genome mutations when discussing different sequencing technologies. These structural variations impacting large segments of the genome are more common than previously appreciated.

Just to bring up one study that is relative to breast cancer, the whole genome sequencing analysis of 130 breast cancer patients revealed that 7% of the population carrying large structural alterations in cancer predisposing genes.

The bottom line is that cancer genome sequencing appears to yield the greatest results for the benefit of families with inherited cancer predispositions, including family members that otherwise might not meet the testing criteria. The human genome is very vast and possesses an enormous landscape of possibility of how the DNA code could be mutated to dysregulate our cells and become cancerous. The majority of these mutations are due to outside environmental factors, but some of these mutations will be inherited. Genome sequencing captures all of the information and thus can find new mutations never observed before, including completely new regions of the human genome that previously might not have even been suspected to be involved in cancer development.

If you desire to test yourself for any heritable predispositions of breast and ovarian cancer, or any other cancer for that matter, genome sequencing will provide the most complete picture of possibility.

I sincerely hope to see even more of such amazing cancer research come out.

This article has been produced by Merogenomics Inc. and edited by Kerri Bryant. Reproduction and reuse of any portion of this content requires Merogenomics Inc. permission and source acknowledgment. It is your responsibility to obtain additional permissions from the third party owners that might be cited by Merogenomics Inc. Merogenomics Inc. disclaims any responsibility for any use you make of content owned by third parties without their permission.

Products and Services Promoted by Merogenomics Inc.

Select target group for DNA testing

Healthy screening |

Undiagnosed diseases |

Cancer |

Prenatal |

Or select popular DNA test

|

|

|

|

Pharmaco-genetic gene panel |

Non-invasive prenatal screening |

Cancer predisposition gene panel |

Full genome |