Cost of cancer treatment - what does it take to beat it?

Dr.M.Raszek

Cancer new ways of investigation

I am an advocate of genome sequencing (decoding of all of the human DNA), especially its application in personalized cancer studies. But the first question that will come to people’s minds is about the cost and utility of such an approach. So I was curious to see how the cost of the genomic profiling of tumors, still a fairly novel approach in the arsenal of cancer treatment, compares with the traditional approach’s costs.

Genomic profiling of cancer is not cheap, but it can be highly valuable if it helps to decode the nature of the cancer and therefore its potential treatment. And there are many options available, from targeted cancer gene panels which cost hundreds of dollars, to whole genome sequencing which can cost thousands of dollars, to a whole battery of diagnostic assessments, from genome sequencing to trancriptome sequencing (the entirety of RNA produced by the tumor at the time of sampling), to the assessment of chromosomal rearrangements (very frequent aberration in cancer cells). All of which can on top of that be correlated with proteomics, the study of protein expression in cancer cells – here the cost will certainly hover around the ten thousand dollar mark at least! These services can be obtained at some clinics as well as at some private laboratories, but are still quite rare.

Whether you get the most affordable tests, or those that are the most expensive, you need experts who can interpret these results, and that is a rare commodity to come across, so on top of the test cost, here you might expect to spend few thousand dollars for the personalized expert analysis. Cancer is specific to each person, in theory no cancer is ever the same, and the molecular profile that drives the cancer development can respond to a specific therapy targeted to those specific broken molecular pathways. Dozens of drug options are now available to specific cancer mutations, paving the way towards the concept of personalized medicine, therapy tailored specifically to each patient’s needs (these also might be an out-of-pocket expense, and they are not cheap either). This is one of the greatest outcomes of the Human Genome Project.

But you need experts to understand the complex intricacies of how different mutations relate to each other, and how they can impact each cancer’s cure, as cancer can harbour a vast array of mutations. And these experts are still quite rare. Very rare. So it is not very likely that an average cancer patient will get access to such targeted therapies, and probably not for many years to come. So in the meantime, cancer patients are destined for the standard therapy options.

I have already written about some published results on the utility of DNA sequencing approach in cancer treatment, although the data on its effectiveness is continuously being gathered and analyzed. If you are lucky enough to get access to cancer targeted therapy, it is not cheap. Your costs can be offset in a variety of ways, depending on the skills of the precision medicine team advocating your behalf. But how do standard therapy costs compare?

Cancer treatment costs equals big bucks

I studied a publication on cancer costs that had been published a few years back, and looked into the cancer treatment costs in 2010 as compared to the projected values for 2020. It was a neat analysis based on the beneficiary claims made between 2001-2006 by any individuals who were diagnosed with cancer between 1975 and 2005, and who were at least 65 years of age during the time window being analyzed (2001-2006). As you can see, the published data is always lagging behind, and not many of these publications seem to be available. But overall, nearly 3 million patient records were measured in 9 different institutions throughout the US, providing a good overview. Furthermore, the authors were savvy enough to divide the costs into three different categories: the initial period of 12 months after the first diagnosis, the last year of life costs, and the continued care costs in between those two periods. The numbers were horrendous (but don’t worry, there was some seriously positive news data too)!

First of all, the total cancer costs were nearly $125 billion US for the 13 cancers in men and the 16 cancers in women that were analyzed! No wonder there are persistent rumors that the “institution” doesn’t want to cure cancer because makes too much profit to loose. But the reality is that cancer is a tough disorder to treat and we have taken massive strides forward in fighting cancers, so these high costs actually are reflecting that! But I will get to that in a moment.

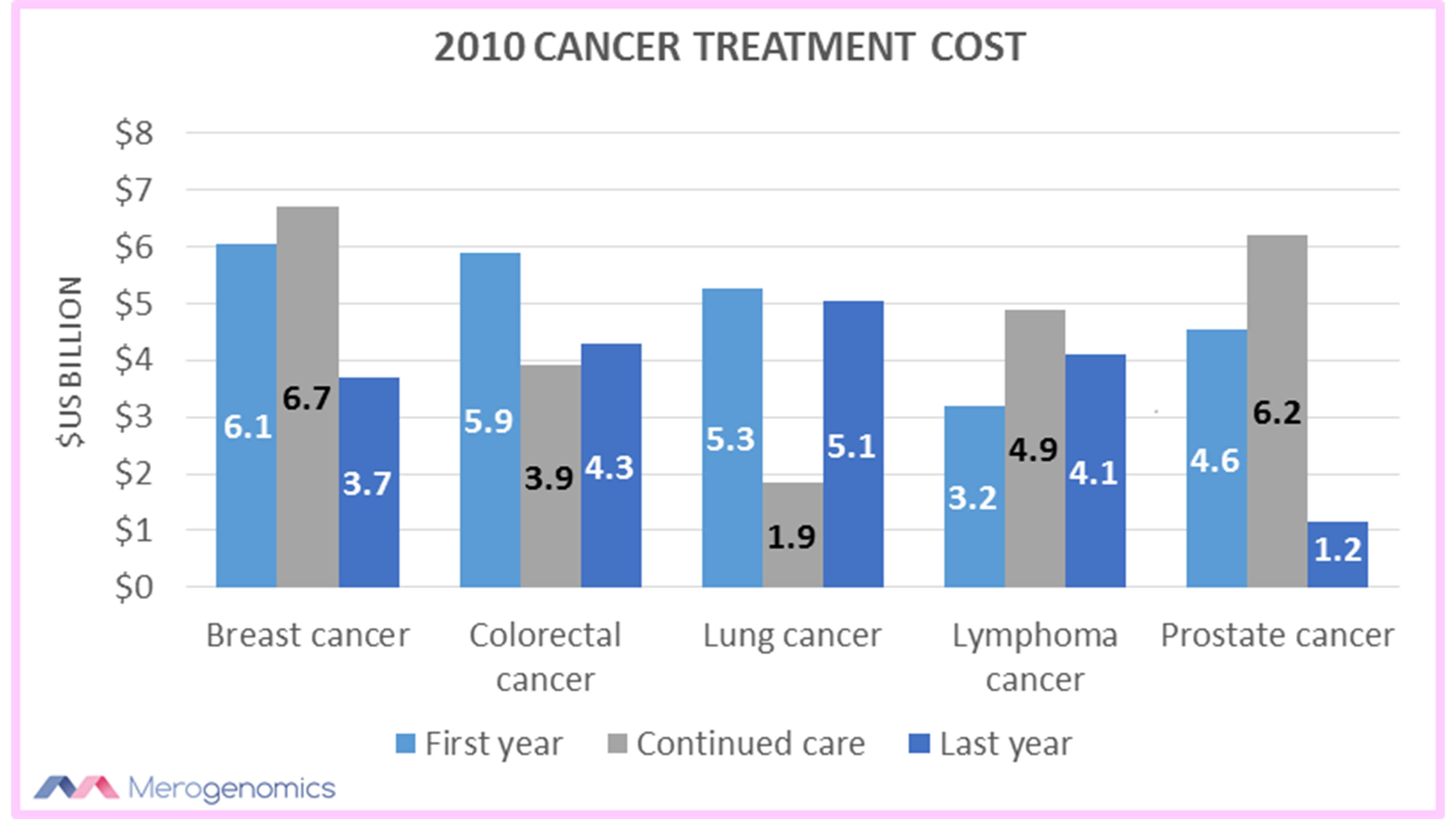

Of these, the top 5 most expensive cancers to treat - all numbering in more than $10 billion/year - are breast, colorectal, lymphoma, lung and prostate, listed in the order from most expensive. Naturally these costs are expected to rise by 2020, and a variety of models were investigated, the simplest being assuming the same costs and only incorporating the continuing trends in population growth and demographic change patterns. This alone should increase the costs by 27%, and if a 2% annual increase in costs are tacked on (the dreaded target of inflation that central banks are attempting to match), then these costs jump to a 39% increase. If you take a 5% increase in annual costs (which might be possible if we continue developing novel medicines thanks to the power of genomics), we are looking at a 66% increase. Something that politicians and policy makers should be taking into account before running for their campaign so eagerly, as affordable quality healthcare is one of the key issues of importance to the general public.

Let’s look at the three different phases of treatment costs that were investigated as it is fascinating, if perhaps at first surprising, information. These can vary dramatically depending upon the nature of cancer. For example, the total national costs of first year breast cancer treatment are just over $6 billion, the continuing care costs are just over quarter of a billion more, but the final year of treatment is closer to $3.75 billion in costs. Compared to that of colorectal cancer, the initial year costs are similar to breast cancer, but the continuation and last year of life costs are closer to $4 billion each. This is starkly different from lung cancer, where the first year of treatment is around $5 billion, continuation drops markedly to $2 billion, and finally the last year of treatment is around $5 billion again. Finally, looking at prostate cancer, a very different pattern is also seen, with initial costs at $4 and a half billion, and a big increase in continuing costs to well over $6 billion/year, but the last year of life costs being dramatically lower at $1 billion. Of these, the continuing treatment for breast and prostate cancer are expected to see the largest increase in cost by 2020.

So why are there such dramatic differences? These obviously depend on the drugs available for treatment, the incidence rate in the population, the chance of survival, age demographics, and a number of other factors. But these overall numbers might seem quite abstract to an individual. It is when these numbers are looked at per individual that the message becomes truly striking. Once again, the costs range depending on the cancer and the age of the patient, and the authors divided the demographics into those above 65 years of age, whom are expected to be diagnosed more often, and those who are younger. The authors also looked at the causes of death in the last year of life costs, and they were categorized as either cancer-related or other.

To list a few examples, the most expensive cancer to treat in both males and females is brain cancer, for any age category. The initial year of treatment runs well above $100 000, with continuing treatment nearing these figures (although typically under $100 000), and shockingly, the last year of life ranging from around $140 000 for people under 65 to over $200 000 for people over 65 (if the cause of death is cancer). At these prices, genomic profiling no longer seems like a prohibitive expense, considering what it can offer.

The cheapest cancer type to treat is melanoma which can range from hundreds of dollars for the initial year for those under 65, and few thousand dollars for those over 65. Continuing costs were between one thousand to two thousand dollars. However the last year of life cost treatment jumps dramatically, depending on age, from around $50 000 in younger individuals, to nearly $100 000 in older individuals! However you cut it, the investigation into the utility of genomic profiling in helping cancer treatment appears crucial even just from the economic point of view. The faster a correct treatment can be obtained, the cheaper the cost of treatment, and the fewer random treatment testings are utilized.

Finally, if we look at the most common cancer in women and men, breast and prostate (just to lighten the mood I will add, respectively), the initial year costs are above $20 000, dropping to two to three thousand dollars per year for continuing treatment, and then rising precipitously to nearly $100 000 in the last year of life. If you are curious about the specific costs for a particular cancer, but do not want to peruse the paper I quoted, you can obtain a good summary in a single table at the National Cancer Institute website. All of these costs were adjusted for all patient deductibles. It would have been very interesting to know how much of these costs had to be incurred by the patient themselves. The bottom line is that cancer treatment is very expensive.

Cancer survival rising

However, there was some very good news presented too which might help explain these rising costs. Everyone has probably heard the sad survival rates of some cancer types, and they are obviously heart-breaking. But luckily, one of the contributing factors to rising treatment costs is actually the increasing length of survival of cancer patients. The relative risk of death within one year of diagnosis shows improvement for all cancer types for both genders, with prostate cancer showing the greatest difference. But that sounds like a small consolation. The authors also presented data on long-term survival, for either 5- or 10-year length periods for breast, prostate, colorectal, lung, and lymphoma, and all show continuous improvement with the exception of lung cancer where the rate of improvement is very shallow.

Breast and prostate cancers show the best odds of long-term survival, with nearly everyone surviving first 5 years, and about 80% or more living for up to 10 years. Colorectal and lymphoma have a 5 year survival that is now in the 70% range, and a 10-year rate of around a 50% range. Lung cancer prognosis remains very poor, reflecting the difficulty in the treatment of this condition. Luckily, the incidence rate has nearly halved for lung cancer. These statistics compare closely to those I discussed in another post, comparing the survival rates between standard and alternative cancer treatments. Let’s hope that these trends will continue to be improved upon, as they have been now for the last 40 years according to the presented data.

As for the presented incidence trends, as measured in the annual percentage change, apart from kidney and melanoma for both genders, the rates are decreasing for almost all cancers types, with ovary cancer showing the best decrease of nearly 5%. This is also great news because not only are more people are successfully treated, but fewer people are actually diagnosed, which shows an important reversal trend for many of the cancers. It would be interesting to investigate what the contributing factors are for such a reversal. This is all very exciting and promising news, and I am certain that the unveiling of genomic technologies will aid in continuing these positive trends in fighting cancer.

This brings a lot of hope for the future of cancer treatment. It appears that cancer diagnosis does not have to be equated with an automatic death sentence. With the growing capabilities of genomic technologies to molecularly categorize cancers towards more refined treatment or management options, there are even greater glimmers of hope for future improvements. And the power of molecular profiling can be enormous, incorporating a variety of biological markers that can be studied for ever greater refined diagnosis. At Merogenomics we can help cancer patients learn about these important options that are available in the market. There is great growth in the diagnostic industry, including the pre-emptive monitoring of cancer development straight from the blood sample, a particularly exciting option that let’s hope one day will become a standard use. Progress is being made, and let’s hope it continues unabated.

This article has been produced by Merogenomics Inc. and edited by Kerri Bryant. Reproduction and reuse of any portion of this content requires Merogenomics Inc. permission and source acknowledgment. It is your responsibility to obtain additional permissions from the third party owners that might be cited by Merogenomics Inc. Merogenomics Inc. disclaims any responsibility for any use you make of content owned by third parties without their permission.

Products and Services Promoted by Merogenomics Inc.

Select target group for DNA testing

Healthy screening |

Undiagnosed diseases |

Cancer |

Prenatal |

Or select popular DNA test

|

|

|

|

Pharmaco-genetic gene panel |

Non-invasive prenatal screening |

Cancer predisposition gene panel |

Full genome |